Ultracrepidarianism is a strange word that describes an all-too familiar thing: opinions and advice on matters outside of one's knowledge.

While HeroX values the insights and disruptive perspectives of ‘outsiders’ and 'misfits,' a quick perusing of any internet forum (looking at you, Yahoo! Answers...) will prove that rampant ultracrepidarianism far outnumbers the distribution of genuine information and valuable advice. This is partly because the deluded conviction doesn't discriminate -- it can be held by people large and small, young and old, poor and rich. These individual instances contribute to the overall deleterious effect of people who insist to others that “they know," when in fact they don't.

The Usual Suspects - All of Us?

We've all see examples, some more conspicuous than others. There's the blustery businessmen declaring that they know how to “do politics," as well as rural agrarians assuming "total understanding" of global economics, and even the suburban academics who interject their moderately well-read opinions as dogma.

As Levitt and Dubner describe in their book Think Like A Freak, so many people insist to know, even in situations where they don’t, because the risk is low and the potential for reward is high. Many of us discover early on in life that there is little consequence for guessing incorrectly, and there are often great rewards for people whom luck favors with a correct guess. Think - most gameshows are basically built around this premise.

Even more unsettling, as the Dunning-Kruger effect demonstrates; the likelihood that someone will voice a view is often inversely correlated to their competence or understanding of the subject. That is to say, the less about a subject someone knows, the more likely they are to overestimate their understanding.

This unfortunate trend fills our world with misinformation. When it becomes difficult to say a simple “I don’t know,” we perpetuate a culture where assumptions reign and facts find themselves dissolved and corrupted by opinions.

Saying “I Don’t Know”

Try it now. Say it out loud. Say “I don’t know." Don’t be defensive or forlorn. Don’t say it with hostility. Just give it a whirl.

It’s ok. You don’t have to know, you can find out. In fact, perhaps one of the greatest strengths of younger "digital native" generations is the immediate reflex to check a reliable source on the internet, via smartphone, when the conversation turns to unfamiliar territory. Of course, it's getting harder and harder to know what constitutes a reliable source anymore, and good luck finding one. Still, admitting what you don’t know creates an opportunity. Contrary to some popular instincts, it doesn’t signify weakness.

As long as you’re willing to approach the world with a growth mindset, you can know, if it's even something about which you care to learn.

Memory and Research

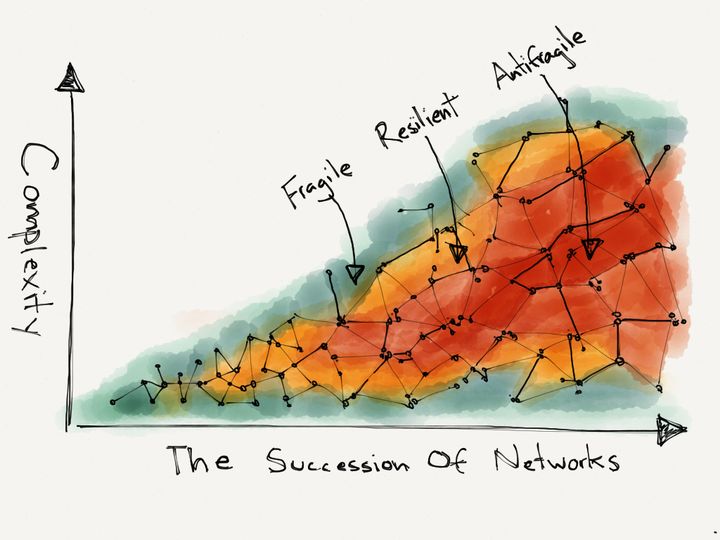

At any given time, this is what your knowledge of the world looks like. No matter how much you learn. It always represents an infinitesimal sliver of what there is to know. And that’s ok. On one hand, as Carol Tavris and many other brain researchers make clear- our perceptions, beliefs, and memories are wrought with fallibility, so it’s responsible and rational to want to hold back and downplay your presumed knowledge until you can verify its accuracy. But, as Josh Foer makes clear, your brain does have an amazing capacity for storing information. So, awareness of mental fallibility doesn’t excuse you to stop trying.

Remember: the breadth and fidelity of your innate knowledge shapes how you think and feel about things in every new moment.

Always Get Two Sources

At least two sources; more is always better when validating facts. But this is where the root of ultracrepidarianism is turned on its head. While the term derides people who to speak outside of their expertise (etymologically speaking: cobbling shoes in particular), it is important to find a diversity set of data before you settle upon your own conclusion.

The paradox of knowing is that “the opposite of a great truth is also true.”